About Lear

Dr. Anthony Stevens, psychiatrist and author

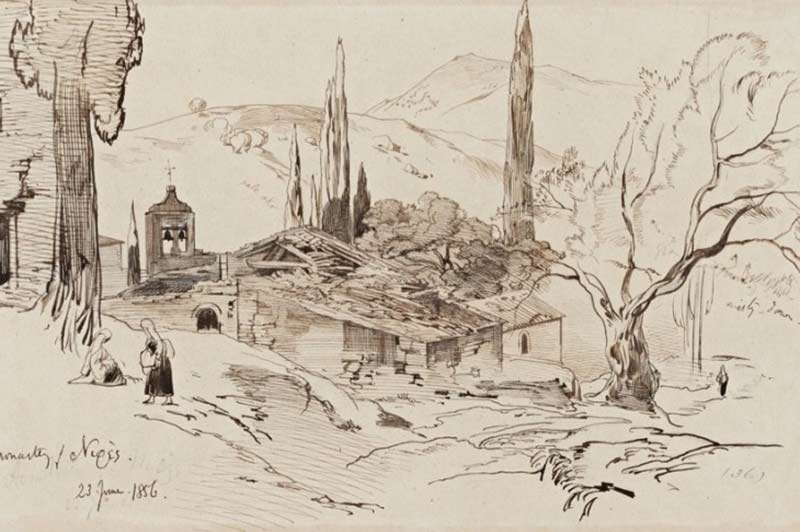

In May 2012 Corfu celebrated the bicentenary of the birth of Edward Lear (1812 – 1888). Though known and loved by generations of children for limericks and nonsense rhymes like ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’, Lear’s chief vocation was as a landscape painter. Working at a time before the camera and the picture postcard had become the favoured means of recording distant places, Lear travelled on foot and horseback through the wilds of mid-nineteenth century Greece, Albania, Southern Italy, the middle East, and elsewhere, making drawings, watercolours, lithographs and paintings of still unspoiled landscapes which he sold to rich clients, the majority of whom could never hope to see them for themselves. Since we can no longer hope to see them either, Lear’s works have become even more precious to us than they were to his contemporaries.

From May 25 to August 31, 2012, some of Lear’s most lyrical works of art, representing scenes from the Ionian Islands, were on display in Corfu’s handsome Palace of St Michael and St George. Corfu held a special place in Lear’s heart and he returned to it again and again, for to him it was “paradise”: “no other spot on earth can be fuller of beauty and of variety of beauty”, he wrote. It is therefore entirely fitting that his bicentenary should be celebrated on the island that he loved so much.

Born in Holloway, then a village on the outskirts of London, on May 12 1812, Edward Lear was the twentieth of twenty-one children produced by Jeremiah Lear, a stockbroker, and his wife, Ann. Exhausted with bearing and rearing so many children (and suffering the grief of losing no less than thirteen of them) Edward’s mother felt unable to cope with him and, when he was four, handed him into the care of his 26 year-old sister Ann, who moved with him into separate accommodation away from the family.

Although Ann proved to be a loving mother-substitute, who remained devoted to Edward for the rest of her life, he never got over the wound inflicted by what he felt to be his mother’s heartless rejection of him. Like many children who have suffered maternal rejection, Edward felt it must be his own fault and as a result he never overcame bitter feelings of personal unattractiveness.

His adult determination to make people laugh with his limericks and to charm them with his art may be seen in part as attempts to compensate for these crippling feelings of ugliness. Ann did all she could to limit the damage, and when she died in 1862, Lear wrote: “Ever all she was to me was good: – and what I should have been unless she had been my mother I dare not think.” Her greatest gift to him was her encouragement of his talent for drawing and painting.

Being a sickly child – he suffered from epilepsy, bronchitis, asthma, and episodes of acute depression – he was never sent away to boarding school and his education was left in the hands of Ann, who taught him to paint flowers, butterflies and birds. He was thus spared the emotionally stultifying effects of a Victorian public school, and was free to develop his imagination in fantasy, in poetry, and in art. As with many creative people, Lear’s personal problems fed his talents: like Cavafy’s barbarians they offered a kind of solution.

In addition to frequent epileptic fits, of which he was always deeply ashamed, he suffered all his life from what would nowadays be diagnosed as “body dysmorphic disorder” – a morbid obsession with his physical appearance (in his case the size of his nose) which sorely affected his social and emotional development, preventing him from finding a soul-mate of either sex with whom he could enjoy a committed and wholly reciprocal relationship.

His limericks caricatured his deformity: in such rhymes as “The Dong with the numinous nose” or the “Old Man on whose nose most birds of the air could repose” he laughed at himself and found relief from the pain that his deformity caused him. It was as if he were saying to the world: “I know you think I’m ugly, but at least I can make you laugh at my ugliness and make it acceptable to you.” The “Old Man” of the limericks is always an outsider, excluded from the ordinary run of humanity because of some physical peculiarity.

Travelling offered another solution. For much of his life Lear was constantly on the move, slogging from country to country over primitive roads and tracks, drawing and painting as he went, sometimes as many as five or six pictures a day.

As he earned his living as a topographical painter he had, of course, to travel to find new subjects, but there was a compulsive quality to this constant activity, as if it was the only way in which he could find peace and satisfaction. “I HATE LIFE,” he wrote, “unless I WORK ALWAYS.” Travelling helped reduce the frequency of his epileptic seizures, and, trekking through magnificent scenery far removed from the demands of conventional society, he found spiritual nourishment in his communion with Mother Nature, the mother who could not reject or abandon him. If he got to Heaven he said he wanted nothing to do with angels: “let me have a park, & a beautiful sea & hill, mountain & river, valley & plain.” He had more to do with them, he wrote in his diary, and they with him, than with mankind.

As a result of the encouragement he received from Ann in childhood, Lear was to retain all his life a passion for working directly from nature. His powers of detailed observation and accurate depiction became apparent in the extraordinary drawings he made as a teenager of the parrots in Regent’s Park Zoo.

These powers were brought to their highest expression in the topographical precision of the landscapes he made of Greece, revealing them to us now as they were then, before the tourists and the developers invaded them. What is more, he created these topographies with the vision of a poet, and it is a mark of his genius that he enables us to share in the aesthetic pleasure he himself experienced as he worked on them. Through the works on display at this unmissable exhibition visitors could delight in the untrammelled beauty of the Ionian world as Lear saw it in his lifetime.