Engraving

Japanese Art Collection

The term ukiyo-e or “pictures of the floating world”

The term ukiyo-e or “pictures of the floating world” was originally related to a Buddhist view of the ephemeral human existence. However, from the 17th to the 19th century it eventually came to suggest a hedonistic approach of the present, the latest fashions, the search for elegance and the everyday life of Edo’s townsmen (modern Tokyo). The woodblock prints depicting this floating, material and ephemeral world are called ukiyo-e.

Ukiyo-E holds an essential position in the Edo capital culture, particularly after the mid-17th century. In that period, illustrated stories written by the Edo bourgeoisie, circulated bound in ehon (book-like volumes). Very often, in the illustration of these books, ukiyo-e woodblock prints were used. However, they gradually evolved into independent works of art that adorned suspension cylinders (kakemono), or into single-sheet prints, used as wishing cards (surimono) or as posters for the promotion of kabuki theatrical plays or actors. All prints were mainly of a commercial character and were widely distributed to the public. Their main themes included Chinese myths, early Samurai myths, everyday city life scenes, as well as portraits of geishas and couples. Also quite popular were travel guides with landscapes as well as works of explicit erotic content (shunga), that were usually circulated illegally.

The art is considered to have been introduced by Hishikawa Moronobu (?-1694), who in the 1670’s created the sumizuri-e (monochrome) prints. Initially, only India ink was used, while some prints were overpainted using a brush. The benizuri-e (two-coloured) are perceived as an innovation of Masanobu (1686-1764), while in the mid-18th century, Suzuki Harunobu (1724?-1770) developed the polychrome print technique known as nishiki-e.

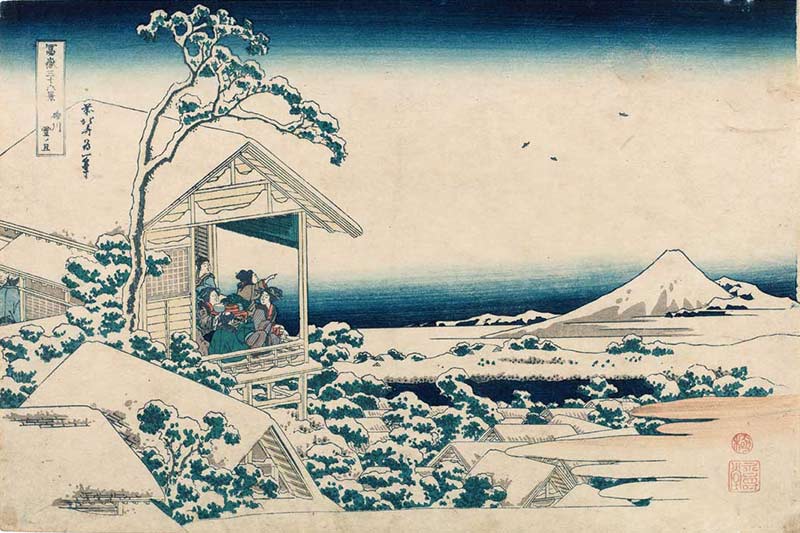

Utamaro, Hokusai, Hiroshige and Sharaku are the most famous artists of the “golden age” of ukiyo-e. During this period, elements of European art are introduced to Japanese prints, mainly a sort of perspective depiction. Utamaro (1753-1806) introduced close-up portraits of geishas and couples, depicted bodies as rather elongate and beautified all forms.

Hokusai (1760-1849) and Hiroshige (1797-1858) mainly dealt with Japanese landscapes. Sharaku (active 1794-1795) is a legendary personality for the Japanese, as very little is documented about his life and he was so widely copied that there are extremely few original works of his in existence today. After the mid-18th century and until recently, the 19th century was considered as the period of decline for ukiyo-e. Today, however, even artists belonging to that period are considered as remarkable ones: the most significant printmaker of that time include Toyokuni (1769-1825) who founded the Utagawa school, but also Kunisada (1786-1865) who was famous even back then.

The artist produced a master drawing in ink

The artist produced a master drawing in ink on paper. An assistant, called a hikko, would then create a tracing (hanshita) of the master. Craftsmen would then glue the hanshita face-down to a block of wood (woodblock) and chisel away the areas where the paper was white. This left the drawing in reverse, as a relief print on the block, but destroyed the hanshita.

The block was subsequently inked and printed, making near facsimiles of the original drawing. A first test copy, called a kyogo-zuri, would be given to the artist for a final check. The prints were in turn glued face-down on as many blocks as the number of final design colours. Each of the woodblocks had a relief area that corresponded to a single colour each time. When all of the woodblocks had been prepared, they were inked with the proper colours and were sequentially impressed onto the same sheet of paper. The final print bore the impressions of each of the blocks, while some were printed more than once to obtain just the right colour depth.

Japonism

Japonism, or Japonisme, the original French term, which is also used in English, is a term for the influence of the arts of Japan on those of the West. Japonism started with the frenzy to collect Japanese art during the second half of the 19th century. In 1854 Japanese ports reopened to trade with the West. Japan ended a long period of national isolation and became open to imports from the West.

Particularly the first samples of print art (ukiyo-e) were to be seen in Paris. Artists who were influenced by Japanese art include Manet, Pierre Bonnard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mary Cassatt, Degas, Renoir, James McNeill Whistler, Monet, van Gogh, Camille Pissarro, Paul Gaugin, Aubrey Beardsley and Klimt. They were especially affected by the lack of perspective and shadow, the flat areas of strong colour, the compositional freedom in placing the subject off-centre, with mostly low diagonal axes to the background.

In terms of music one can say that Japonism was used among others in Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, and Turandot, as well as in Claude Debussy’s La mer.